Joaquin Phoenix’s transformation into Joker, body and soul, only enhances his unpredictably violent aura which has everybody on edge. The maniacal laugh of Phoenix’s committed performance lingers long after the last scene. Phoenix plays Arthur Fleck who, among other problems, has a condition called PBA, Pseudo Bulber Affect, which causes sufferers to laugh or cry uncontrollably at inappropriate times.

Director Todd Phillips (War Dogs, The Hangover movies, School for Scoundrels) makes this Phoenix’ stage, completely. It is a re-imagining of the Joker first seen as Batman’s nemesis in DC comics that has been portrayed many times. There are few frames wasted without Phoenix in the mix. Phillips co-wrote this with Scott Silver (The Finest Hour, 8 Mile). The images outweigh the dialogue but there are several lines that help explain Joker’s descension into madness. “I used to think that my life was a tragedy, but now I realize, it’s a comedy.”

Phoenix’s characterization is simply frightening. He lost 52 pounds for the role and looks bony and emaciated in the scenes with his shirt off. His hair is long, unkempt and greasy. It’s obvious he doesn’t think much of himself until later in the film when he emerges as the full fledged Joker. That’s when his body movement and body language changes completely well choreographed in a dance on an outdoor mountain of stairs used metaphorically frequently in the film. Phoenix performs a lithe dance that looks like a cross between ballet and Tai Chi that’s impressive, showing some inner beauty.

This film tackles a myriad of issues, especially mental illness. Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix) is working as a clown living in a slum with his sickly mother (Frances Conroy, TV’s Arrested Development, American Horror Story). He works for a clown temp agency. He chases some teens who bullied and beat him up after they stole the sign he needed for his job. This is just the first in a long string of degrading episodes taking him down the path to hate-laced insanity.

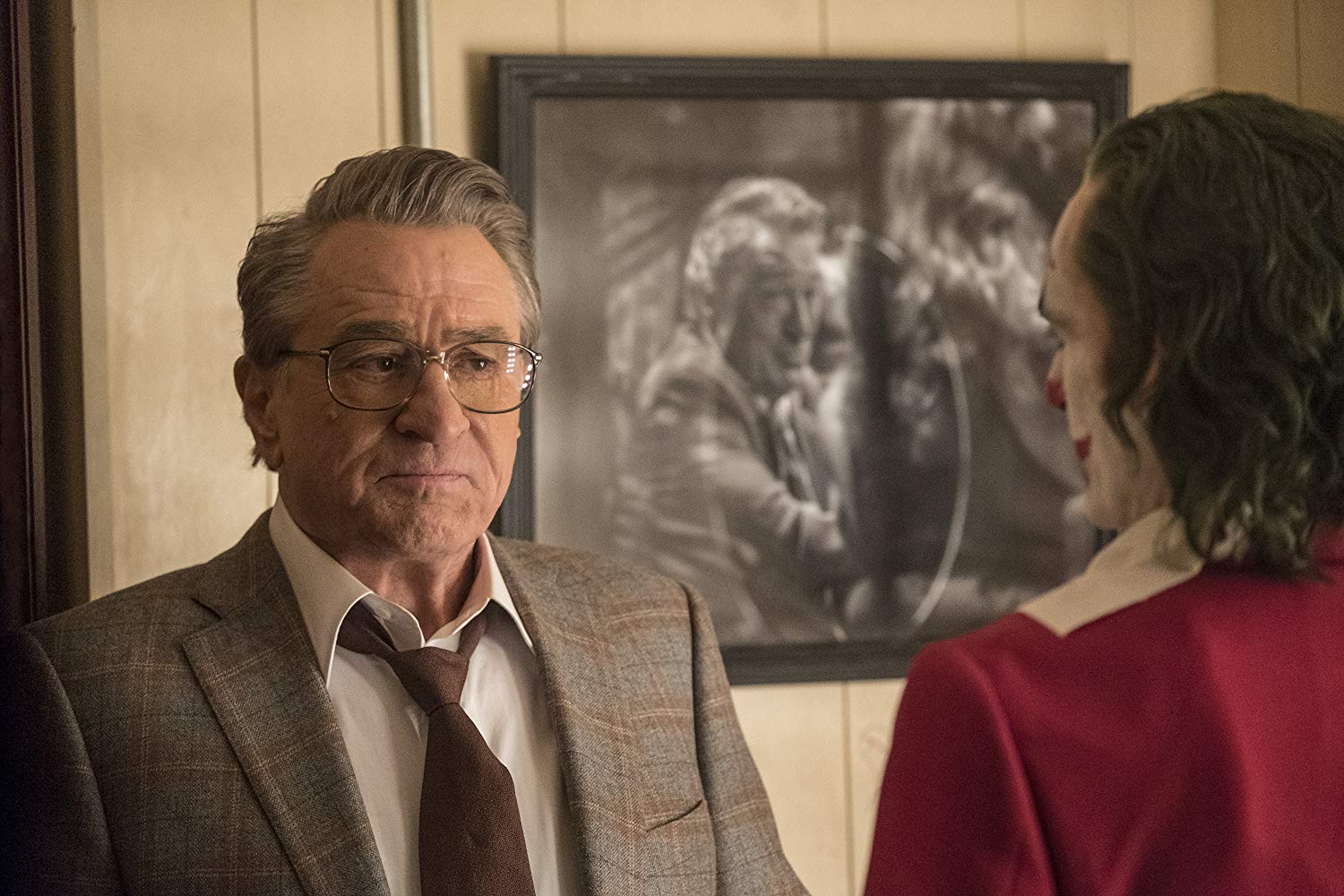

He lives in rat infested, garbage-choked, slum in corrupt Gotham City, which doesn’t help Arthur in the job market. His dream is to be a comedian and get a guest-spot on the popular Murray Franklin (Robert De Niro) late night TV talk show. Set in 1981, De Niro is straight forward in his portrayal of this Johnny Carson type character. The casting choice, however, is fascinating considering De Niro was on the other side of the talk show desk as Rupert Pupkin to Jerry Lewis’ host in The King of Comedy.

Fleck sees a Black female mental health counselor, who is losing her job and is unresponsive. The Social Service agency is being eliminated because of funding and is another indication of the huge gulf between the powerful and the powerless. Fleck is being victimized again. He points out his problem, “The worst part of having a mental illness is people expect you to behave as if you don’t.”

Phillips introduces more issues besides bullying and mental health through images and incidents throughout the film. Bullying surfaces again on a train where three young Wall Street Types are bothering a woman. Fleck gets involved and the incident on the train sets him on the course of becoming a homicidal maniac. This becomes a case of rich vs. poor and for family reasons, he pursues Thomas Wayne, the billionaire he thinks he has some tie to. He also encounters young Bruce. As Fleck descends deeper into insanity, the film becomes more violent.

Though the bodycount may not be as high as John Wick, the murders are more disturbing, partly because of how and when you least expect them. In a large part, this is due to the camera work of Lawrence Sher (War Dogs, Godzilla: King of the Monsters, The Hangover). His camera captures Phoenix’s physical actions as well as the extreme closeups of the actor’s face as he unravels. The scene of him climbing into a refrigerator during a period of frustration is noteworthy. The camera seems to be lifted off it’s mount to go hand-held making an uneven truck toward the fridge door. It’s a short scene, unexplained, but makes an impact. So is Phoenix’s movement on the stairs finally dressed colorfully as the Joker, dancing to Frank Sinatra’s “That’s Life.” Music Director, Hildur Grônadóttir, provides ominous sounds to increase tension, but also adds some song choices for background that are too obvious. “That’s Life” is played 3 times, “White Room” (Cream) in the Mental Hospital, and “Send in the Clowns” over the credits were just too obvious.

Phillips has created a stand-alone version and Phoenix asserts he will not be the Joker ever again. But this film has elements that reference Scorsese and De Niro films including Taxi Driver and The Godfather, as well as Network where the main character becomes a news sensation.

Yes, this film is disturbing and violent, but it deals with serious issues. More than anything else about this film, it’s Joaquin Phoenix’ performance that stands out. For anyone trying to set up a comparison with other actors who have portrayed the Joker, including Heath Ledger, don’t. The only thing shared between them is that each had their own unique interpretation of this agent of chaos. Each leaves their mark as a mile post for this cinematic genre. Even though based on a cartoon character, there’s nothing cartoonish about this movie.

Warner Bros. 122 minutes R